by Hans DePold, town historian

(Published in the Bolton Community News, December 2005)

The homes of Bolton's founders present concrete symbols of an idyllic yet very modest past. The abundance of wood and their builders' desire for sturdy construction made timber frame houses (post-and-beam construction) most popular. In the early 1700s, Bolton's settlers were constructing what we now think of as the quintessential Colonial. These homes were two stories high with gables on the side and an entry door at the center. To conserve heat, a massive chimney ran through the center, and the ceiling height was usually less than 7 feet. Tall men had to duck their heads often in those days.

On November 11, 2005 several selectmen, Historical Society members, and the town attorney carefully examined the Rose Farm house, which originally was Bolton's minister's house. Later, when what I had seen began to sink in, I became 99 percent convinced that the core of the Rose Farm house is still the original house of Reverend George Colton, built around 1725 for the first church minister, Reverend Thomas White.

I believe our local history may have fallen well short of archaeological truth. For instance, in 1970 at our 250th Founder's Day celebration the Bolton map of historic sites had the encampment listed #1 but it was located on Brandy Street near abandoned Bailey Road. In 1994, I discovered the true location and the French Ambassador and French Consul agreed and wrote letters to the Governor. The State Historical Preservation Office (SHPO) then also checked and agreed and Representative Pamela Sawyer got the funding for SHPO to document the locations of all the encampments in Connecticut. The SHPO archaeological dig in 1999 proved the Rose Farm was the actual site of the encampments. In 1998 I discovered from General Washington's itinerary and diary that he had lunch in the house with Reverend Colton on March 4, 1781, yet the town had no record of it. In fact, Reverend Colton and the town archives made no comments about the 5,000 French troops while they were camped here four days, or Washington's two visits--first as the commanding general of the Continental Army and second when he passed through on his Presidential tour. Reverend Colton was so modest that today we would not know what he looked like had he not been sketched and painted without his knowledge.

There is only one cryptic note that I have ever seen that refers to any fire at the Rose Farm house, and it was only written much later. The folk tales say the house looks the way it does because it burned and was rebuilt in the Federalist style between 1830 and 1840 and subsequently remodeled. Well, that is largely false. We saw that the core of the house is most definitely Colonial style, not Federalist. Furthermore, it has very low ceilings that were in style in 1725 and very much out of style in 1830. I saw no hard evidence of a fire--no charring, no foundation stones damaged by intense heat, no chimney heat damage or charring. Yet it is possible that there may indeed have been a fire because the roof area around the chimney was definitely replaced, and there may be evidence concealed in the walls, or buried. The attic window looks like an original 8-over-12-paned window that dates to the early 1700s. At least one floor looks like original wide-plank chestnut wood. More than 60 percent of the core of the house looks original to me because the repairs are very plain to see. Most of the windows and doors were replaced over time and the exterior was definitely 90 percent "remuddled." That is why it is difficult to see that the core of the house is still the original, extremely historic Colonial house.

I am convinced now that we have just rediscovered a diamond in the rough. We must have it authenticated. It is on the National Registers of Historic Places, but no one during those processes examined the house closely. This is such an important discovery that we should be able to find experts who would be honored to authenticate it at little or no cost to the town.

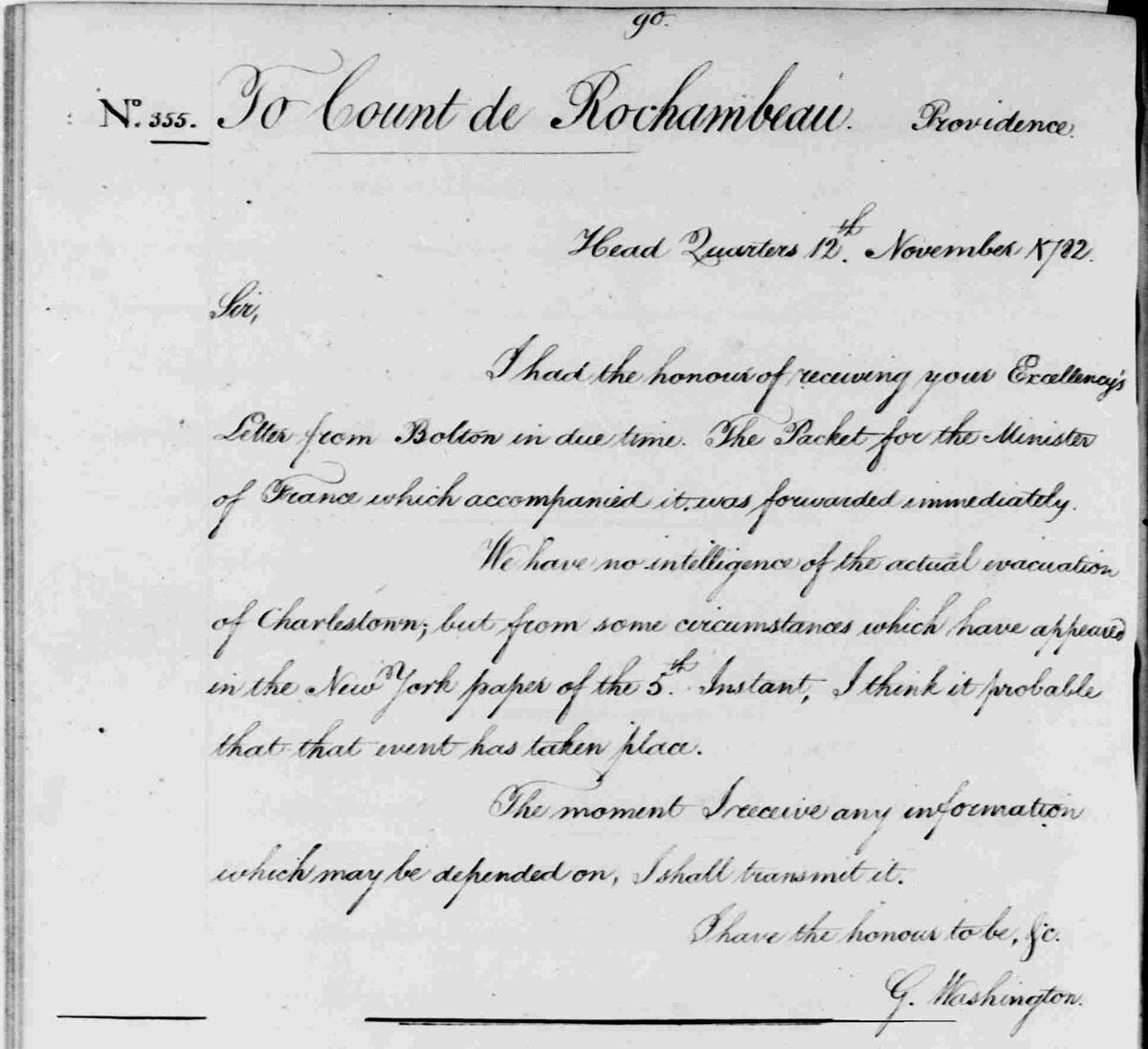

If I am correct, this Bolton asset will be of extraordinary national historic value. Washington ordered Rochambeau to return by the same route they had used to attack the British at Yorktown, Virginia, and to once again feint an attack on British-occupied New York City. The objective of the return march was to force the British to reinforce and defend the city by withdrawing troops from Charleston and other places, thereby freeing all the other states. Yale president Ezra Styles wrote that he and Rochambeau had supper with Reverend Colton on Rochambeau's return trip, on November 4, 1782. Rochambeau then retired to Colton's home to complete his report on the war in America. He posted his report packet from Bolton to General Washington the next day as evidenced by Washington's letter of confirmation on November 12, 1782.

On November 11, 2005 as I peered into a small second-floor bedroom of the Rose Farm house, I could almost sense General Rochambeau there at the desk writing that report.